Charles I of England did not share his father's enthusiasm for plantation and was considerably more concerned with raising funds to wage a possible war. Growing problems with the Scottish church led Charles to insist the Scots settlers in Ulster take the Black Oath affirming their loyalty to the Crown. Planter-Crown relations suffered as families, such as the Acheson's, were affronted by the King's doubt. Relations deteriorated further with the rumour that Charles I was considering arming Catholic inhabitants to wage war against the wishes of his Parliament. As the King clashed with his Parliament, native Irish realised that "England's difficulty was Ireland's opportunity".

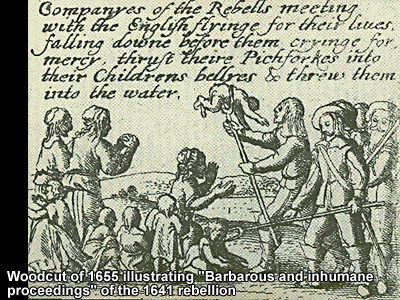

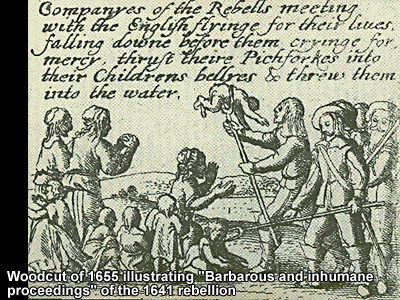

Early in the evening of October 23rd 1641, Bishop Leslie of Down received news that the Irish had risen in rebellion and by stealth had captured the forts at Charlemont and Dungannon. Soon troops under the command of Sir Phelim O'Neill captured Newry and were moving to attack Belfast. The insurrectionists were operating in the belief that Dublin Castle had been captured and that the Gaelic lords of Dublin would support the rebellion. This proved not to be the case but, despite their miscalculation, the rebellion was sustained with the objective of overthrowing plantation in Ulster.

As a region of dense plantation, the area around the fledgling town of Markethill was an area that suffered during the rebellion. Seeking revenge for his defeat at Castlederg Sir Phelim O'Neill ordered Mulmory MacDonell to "Kill all the English and Scots within the Parishes of Mullabrack, Loughgilly and Kilcluney". MacDonell's troops burned the bawns on the Acheson and Hamilton properties and defaced the Hamilton memorial plaque in the Church of Ireland at Mullabrack. The Rectors of Mullabrack and Loughgilly, Rev.Mercer and Rev.Burns, were both murdered. In February 1642, General Robert Monro was sent from Scotland to protect Scots settlers and bring a conclusion to the rebellion as the country descended into civil war.

A commission of eight clergymen was set up to record losses suffered by Protestant settlers. Depositions recorded are held in the libraries of Trinity College, Dublin. Some are unbelievably fantastical but others provide details of massacres. Modern historians estimate settler deaths as approximately 12 000. One of those who testified to the commission was James Shaw, innkeeper of Markethill:

"And he saith, that during the time he, this deponent, was so restrained and stayed amongst the rebels, he observed and well knew that the greatest part of the rebels in the county of Armagh went to besiege the Castle of Augher, where they were repulsed, and divers of the rebel O'Neils slain; in revenge whereof, the grand rebel, Sir Phelim O'Neil, knt., gave direction and warrant to one Maolmurry McDonnell, a most cruel and merciless rebel, to kill all the English and Scottish men within three parishes aforesaid; whereupon that bloody rebel, with his soldiers, most cruelly murdered within a musket shot of this deponent's own house, twenty-seven men of Scottish and English protestants, and left them lying there, when this deponent, to the great hazard of his life, and by the assistance of two of the said Turlogh Oge's servants, commanded by said Turlogh to assist him, buried them all, not daring to carry them to the church or churchyard. And he, the said Maolmurry, and his soldiers had also murdered this deponent and his family, as this deponent is verily persuaded, but that they were rescued from him by the said Turlogh Oge O'Neil, and afterwards protected by the said Sir Phelim.

"And those wicked, rebellious murderers, about six weeks after, gathered all the Protestants---men, women, and children---together, of those three parishes by sevenscore or eightscore at a time, and forced and drew them away from thence into the county of Down, and there drown them in a lough near Loughbricklan, and at a place called Scarvagh, and other places thereabouts. So that indeed many British families in those three parishes were wholly depopulated, both men, women, and children, none escaping that were sent out of those parishes, but such as were saved by or by the means of the said Turlogh Oge O'Neil, which were about three or four hundred. And this examt. Further saith, that many of the mere Irish rebels, in the time of this deponent's staying in restraint amongst them, told him very often, and it was quite a common report amongst them, that all those that lived about the bridge of Portadown were so affrighted with the cries and noise made there by some spirits or visions, for revenge, that they durst not stay there, but fled away, and this deponent observed and saw them to come thence so affrighted (as they professed) to Market Hill, saying they durst not stay at Portadown, or return there for fear of those cries and spirits, but took ground and made creaghts in or near the said parish of Mullenabrack [Mullabrack]. And this deponent saith, that two of the irish rebels, whereof one was of the name of Magennis, of the county of Down, said within this deponent's hearing, and swore he was present when a bloody villain, attempting after he had drowned many others to drown Mrs. Campbell, a goodly, proper gentlewoman, and a protestant, and for that offering violently to thrust her into the water, she suddenly laid hold of and caught him in her arms, that wicked rebel, and they both falling into the water, she held him there fast, until they were both drowned."

The deposition of Mary Twyford in 1642 alleges other atrocities committed by the rebels within Kilcluney parish,

Further in her deposition, she relates,

Civil war in Ireland mirrored events in England. Though the war in England had its roots in English difficulties, events in Ireland did little to help. During the rebellion in Ireland, Sir Phelim O'Neill insisted he had been encouraged to take action by Charles I. Though the King denied the report, he had alienated enough nobles to render the accusation believable and gave Parliament another reason to dispense with his monarchy.

Back in Ireland, the forces of Monro and O'Neill continued to clash. En route to Benburb, General Monro marched his troops through the village of Hamiltonsbawn. Supported by Scots settlers in the area, the soldiers received food and shelter.

The locality demonstrated remarkable resilience with the rebuilding of the Gate Lodge of the Acheson Estate in 1646. With the execution of Charles I, and the establishment of the Commonwealth in 1649, Cromwell came to Ireland and set about exacting revenge for the massacres of 1641. Estimates of casulaties of the native Irish by modern historians (in conflict and from famine and disease resulting from the conflict) range from 200 000 to 618 000 (or 41% of the native population). The war was officially ended by 1652 but sustained Cromwellian repression of the Catholic religion followed.

Restoration of the monarchy brought some respite, as Catholics were once again allowed to celebrate their religion in public and Presbyterians were granted some recognition of their faith. On this, see also the page on Presbyteriansm and Covenanters.

In the accompanying audio recording, Sam Hetherington talks about Eoghan Ruadh O'Neill, Oliver Cromwell, Richard Cromwell and the Restoration (2mins 14s).

Use the audio controller to listen to this talk, given in 2013.